Leaving the Container: Small Ceremonies

Night in this World, a Journey – Part VII (Parts I-VI available here)

By Sharon English

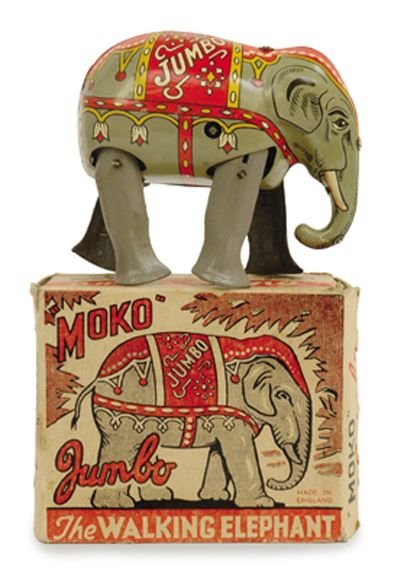

For years I’ve been drawn to the story of Jumbo the Elephant. Though I don’t recall when, at some point I saw the life-sized statue of Jumbo erected in St. Thomas, Ontario, and learned that the most famous of Elephants died violently in this small town just up the road from London, where I was born and raised.

Jumbo’s biography speaks to the particular suffering experienced by beings who have the misfortune of becoming a cultural fetish. Such was the fascination with Jumbo that his name passed into the English language – though I suspect most people today don’t realize that the adjective applied to everything from junk food to crosswords was the name of a real creature: an African bush elephant, sold as a baby to animal traffickers who made him a star; who was fought over, abused, and overindulged like one; and who met the same dramatic and untimely end of many a Hollywood icon.

Jumbo statue erected in St. Thomas, Ontario in 1985, on the 100th anniversary of his death.

Jumbo was about 25, still a young elephant, when he was struck and killed by a freight train on September 15, 1885. As an infant calf, he’d lost his mother to poaching. Her killers pawned this valuable orphan to a German dealer, who transported the baby from his homeland in the arid Sudan across the Mediterranean to the Paris Zoo, who later sold him to the London Zoo. On the damper side of the Channel young Jumbo became a sensation, giving countless rides on his back to piles of British children, and heavier folks. He had no elephant companion. And as he entered puberty he got hard to handle—even with all the whisky he drank. In a controversial decision, the zoo sold him to PT Barnum. Jumbo again crossed a sea, and in North America travelled in Barnum’s circus with the other captive animals (including elephants). That’s how he ended up in St. Thomas, crossing the tracks after a performance, on a night when no one expected a train.

Note the missing tusks: Jumbo first broke, then ground down his tusks while in captivity.

Last month, in a twist of personal fate, I found myself not in my usual place for the past twenty years – a university classroom – but in London, ON, staying at my parents’ house. For a while I’ve wanted to make a pilgrimage of sorts to the statue in St. Thomas. Then I discovered I could do so on the anniversary of Jumbo’s death. Something was lining up.

It was a warm and sunny Friday afternoon when I arrived and set up my simple ceremony: some seasonal flowers, a stick of sage incense. The statue stands on a ridge at the edge of town, an energetic Jumbo looking out on the wooded valley. The street’s residential; no one was about. I re-read the public plaque, stood in contemplation, and tried to let all the soreness of Jumbo’s story be present – including the tensions inherent in this statue, which is both tribute and claim to a piece of Jumbo’s fame.

Crickets and traffic hummed. Smoke curled from the incense.

And then, they began to arrive.

First was a grandmother with platinum hair, her daughter, and two grandchildren who jumped up excitedly on the plinth. Grandmother noticed the flowers, the incense, and me. Why yes, I did that … It’s the anniversary of Jumbo’s death today. It is? Going over to read the plaque. Isn’t that something, and how nice of you … Can you take our picture? Can we take one for you? Oh, sure. We’re on a first name basis now. Things feel a little surreal. Is this an intrusion, or part of the ceremony? If you decide it’s all ceremony, you’ll meet it appropriately. More cars pull into the parking lot, two couples approach and Grandmother draws their attention to the flowers, the incense, the anniversary, me. Oh! Can you take our picture? And ours? I handle phone after phone, take photo after photo of poses before Jumbo’s image. The incense burns. I say little this whole time. Visitors shuffle and now a second Grandmother with silver hair stands at my side, talking about our relationships with animals and God, values of peace, love, and non-judgment. She hugs me goodbye.

The next arrivals keep to themselves. The incense has burned low and I feel released from whatever just happened. Ceremony is done.

***

I returned to Nova Scotia for the fall equinox, so I could keep to my new tradition of holding fires on the points of the solar year. Hurricane/post-tropical storm Lee blew through days before, considerably milder than the hurricane of 2022. Nonetheless, Lee left his mark in felled trees and one huge, unanticipated shock. My friends sent me a photograph before I went home, so I’d be prepared: there was our most beloved elder tree, Grandfather Ash, with his central trunk broken and dangling. I couldn’t believe it. What a loss, what a blow to the heart.

In fact, Grandfather Ash has become a heart.

To honour the equinox, my friend and co-resident Kerry and I had talked about having a drum circle around the fire. But what is a drum circle, how does one do it? We didn’t know. We just wanted something ceremonial, sacred. It felt important. So we wrote an invitation and sent it out, wondering who’d come to Urbania for a vague event on a Thursday night. At five o’clock on September 21, I lit the fire.

At six o’clock a car pulled up with two women from the city whom neither of us knew. A second car brought two more from the lands across the river. (One, it turned out later, had plenty of drum circle experience but was shy about saying so.) With Shane providing a steady beat we started, feeling our way through the awkwardness of strangers doing the unfamiliar. And slowly we came into coherence and connection, like group breathing.

Dusk deepened. I was aware of the many trees beyond our harvest fire’s glow: Aspens, Maples, Willows and Spruces, Birches, Apples and Oaks; those standing and those fallen; and those like Grandfather Ash and Grandmother Apple, wounded yet still living. We drummed for an hour, talked a little, drummed again. The women from across the river sang songs in Mi’kmaw, the language of their relatives and ancestors, which was likely the first such music heard again on this land in over a century. I thought of how the songs and beats, the smoke, offerings and laughter were watering this place, and now, of how making these small ceremonies of reverence, out in the open, feels as essential as rain for this human, embedded in a culture parched of public spiritual life. It feels like digging myself out of a container I’ve been living inside since birth and seeing all those misshapen, bound-up roots.